The CPI reaching 9.1% in June made it clear that the inflation crisis gripping the nation is as bad as it’s been in 40 years. Despite lines from the chattering classes about inflation having “peaked” or being “transitory,” the truth is that there is little reason to think that high inflation will not be with us for the foreseeable future.

The problem is that every fundamental cause of inflation shows few signs of slowing.

If we look at the famous quantitative theory of money, we can evaluate each component separately.

M x V = P x T

M (money supply) x V (velocity) = P (price level) x T (volume of transactions)

P is the price level (i.e., how much inflation there is), so we can ignore that one and look at the other three.

Money (M)

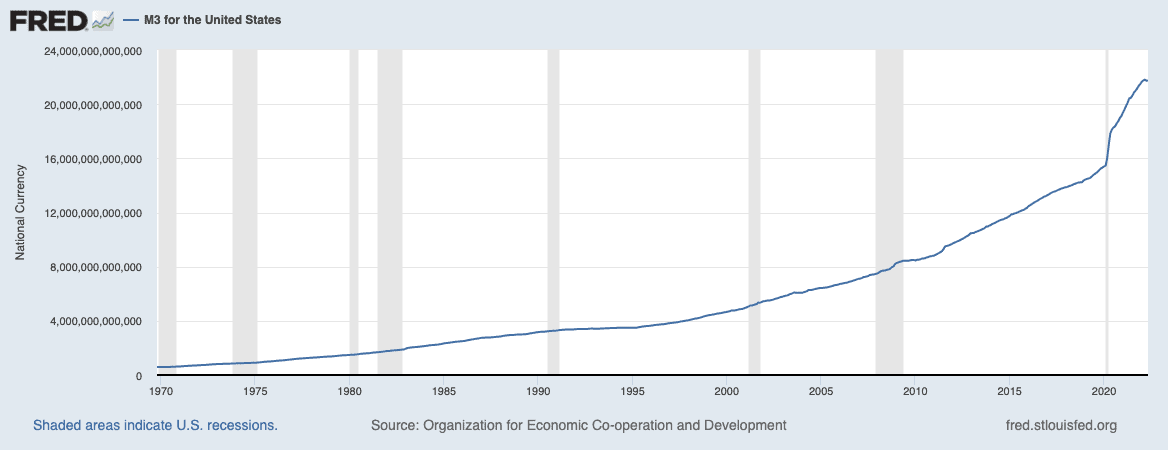

Famous economist Milton Friedman once said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” While economists quibble over whether that’s an overstatement or not, no one doubts that all else being equal, more money in the economy equals higher prices. And, well, there’s a lot more money in the economy these days.

In March of 2021, Congress passed a $1.9 trillion stimulus package that was on the heels of a $900 billion package in December 2020, which was in the wake of the $2.2 trillion CARES Act passed in March 2020. All of these massive bills were to lessen the fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Before March 2020, there had never been a single trillion-dollar bill passed in U.S. history.

For comparison’s sake, the entire federal budget is $6.82 trillion. The country ran a record $2.8 trillion deficit in 2021 and, as one column unironically (albeit rather humorously) put it, “The U.S. deficit will shrink to $1 trillion this year.”

“Shrink.”

In addition, when the pandemic broke out, Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell lowered the discount rate to 0% and took the unprecedented step to remove bank reserve requirements.

It’s too complicated to go into the mechanics in this article, but new loans actually create new money. (An explanation of how this works can be found here.) By the same token, loans being paid off or going into default destroys money.

If you remember back to March 2020, pretty much everyone thought that the real estate market and the broader economy would collapse. These moves were made to halt or at least slow that inevitable collapse. But the collapse never came.

Instead, the economy was just littered with cash. TechStartups.com estimated that 80% of all dollars in circulation were printed since the beginning of 2020! While that figure has been challenged, what is plain as day is that the money supply has increased dramatically, as this chart from the St. Louis Fed shows:

Again, all things being equal, more money means more inflation. Oh boy, do we have more money.

Velocity (V)

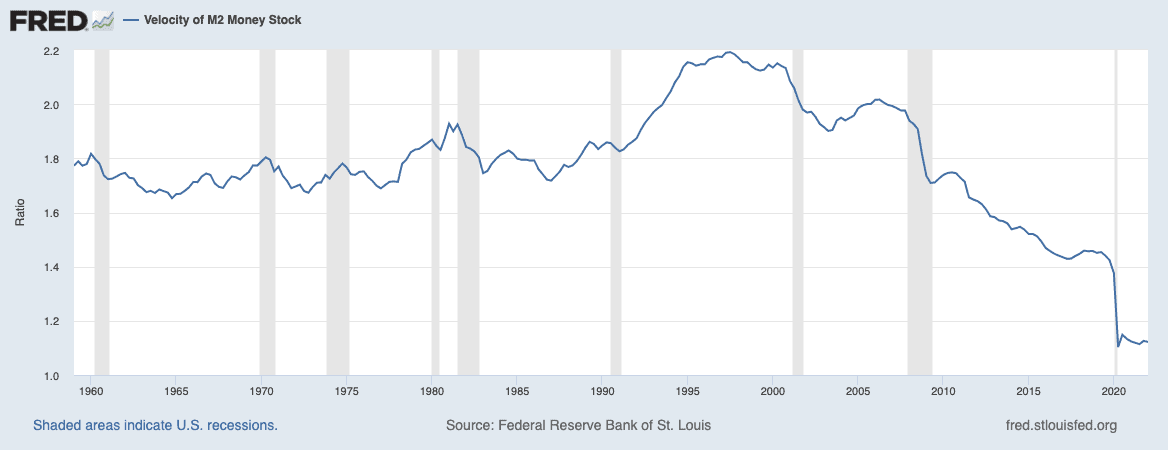

Velocity is how fast money is spent. As I explained in a previous article,

“So, for example, if I have one dollar and buy a widget from you, and then you turn around and buy a piece of candy from John, that dollar has been used in two transactions. The velocity of that dollar stands at two, and there might as well have been $2 in the economy. On the other hand, if I had two dollars and then bought a widget from you and a piece of candy from John and both of you held that dollar, the velocity of each dollar is one.”

Currently, the velocity of money is still near historic lows. As Trading Economics notes, “Velocity of M2 Money Stock was 1.12200 Ratio in January of 2022, according to the United States Federal Reserve. Historically, United States – Velocity of M2 Money Stock reached a record high of 2.19200 in July of 1997 and a record low of 1.10300 in April of 2020.”

Again, the St. Louis Fed makes this painfully clear.

Recessions tend to reduce velocity and thereby lower inflation, so while the U.S. is likely in a recession already, how much lower can the velocity of money go? Especially with unemployment at only 3.6% in June, it would seem more likely that velocity will go up and increase inflation than continue to decline.

With inflation at 9.1% while velocity is as low as it is, this bodes ill for any last hopes of inflation being transitory.

Volume of Transactions (T)

This is the other side of the equation. Whereas if the amount of money or velocity goes up, prices go up, if the volume of transactions goes up, prices go down, and vice versa.

This is where supply chain issues related to the after-effects of the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns and the economic sanctions related to the war in Ukraine come into play.

The war in Ukraine was particularly noteworthy for its effects on gas prices, which are a significant driver of inflation since so many things are shipped over great distances. Higher gas prices make travel, logistics, and commerce more expensive, eventually passing on to the consumer.

While we can all hope for a quick end to the war in Ukraine, the geopolitical battle lines appear to have been drawn for the foreseeable future. The litany of sanctions put on Russia are unlikely to be lifted even if the war were to end tomorrow. It seems like a new cold war appears to be on the horizon (if it hasn’t already begun). This has led to what could be seen as a China-led trade bloc and the world fragmenting into specific factions. This is even happening with the Internet in what is now referred to as the “splinternet.”

In short, while globalization may not be breaking down, it’s certainly stalling, and sales volume is likely to continue to stall with it.

And while gas prices will likely come down soon after the war in Ukraine ends, who knows when that will be and if the new cold war will shrink global trade and continue to keep production costs higher than they would have otherwise been.

Another Variable: Political Will

The last time the United States dealt with high inflation was between 1973 and 1982. Right off the bat, it should be noted that that was a full decade of high inflation. Once inflation takes hold, it’s very hard to get rid of as businesses and individuals begin to anticipate continued inflation. Workers expect higher prices for goods, so they demand higher salaries. Companies, in turn, expect higher labor costs, so they increase prices again, and so on.

The only way to get rid of it is to decrease the money supply drastically, decrease velocity (unlikely given how low it already is), or increase productivity (unlikely to change substantially in the near future).

So that means to halt inflation, we would need to cool down the economy and reduce the amount of money in circulation. The most efficient way to do that would be to increase interest rates, which slows lending and the money creation that comes along with lending. And this is exactly what the Federal Reserve is doing, sort of.

In April 2022, Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell announced the Fed would increase the discount rate to 1.9% by the end of 2022 and 2.8% by the end of 2023. Already, they’re exceeding that pace as the discount rate stands at 1.75%, with more increases expected this year.

The issue here is that the discount rate is still near historic lows. Even if they get up to 2.8%, that is still below the historical average.

Final Thoughts

To “break the back of inflation” in the 70s and early 80s, former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volker had to increase the discount rate into the teens. It was not uncommon for 30-year fixed mortgages to be over 15%, with the average hitting 18.5% in 1981.

Not surprisingly, this threw the United States into a deep, albeit short, recession in 1982.

While the U.S. is likely already in a shallow recession, raising interest rates as Volcker did would probably send the economy over a cliff into something akin to the 2008 Great Recession or worse.

But there are more concerns than just economic. For one, the United States has astronomically more debt now than in the early 1980s ($29.6 trillion in 2021 vs $908 billion in 1980). Increasing rates will increase the interest payments on the federal debt, which could become unsustainable, especially if the country is plunged into a deep recession and tax receipts subsequently fall.

Furthermore, political divisions are as high as they have been in the postwar era, with Democrats and Republicans growing further and further apart. A deep recession is not something any politician or Federal Reserve chairman wants to add to this already volatile brew.

On the other hand, high inflation erodes the federal deficit. While inflation is extremely damaging to regular people, particularly the poor and those on fixed incomes, it is less of a punch in the gut than the deep recession that would likely be required to stop it in short order.

In other words, there’s no easy way to stop inflation now, and there certainly isn’t any political will to do so. Thereby, there’s no reason to think it won’t be with us for quite some time.

On The Market is presented by Fundrise

Fundrise is revolutionizing how you invest in real estate.

With direct-access to high-quality real estate investments, Fundrise allows you to build, manage, and grow a portfolio at the touch of a button. Combining innovation with expertise, Fundrise maximizes your long-term return potential and has quickly become America’s largest direct-to-investor real estate investing platform.